Abstract

Defining the perfect diet has been a laborious task for the nutritional sciences for decades. Likewise, specifying the optimal intake of vitamins and minerals is difficult in the face of continuing nutrient research. This makes giving concrete nutrient recommendations challenging. For most nutrients, there is a large therapeutic range within which the average person will receive benefit and simultaneously remain below the threshold that can yield adverse events. It is one matter to define nutrient recommendations and another to actually consume the recommended dosages through the course of a normal day with typical foods. The notion that you will satisfy all physiological needs of the body for proper and ideal nutrient intake with food alone is impractical and outdated. Some of the obstacles to proper eating and ideal nutrient intake include insufficient food intake, increased needs that are not met by food alone, and dislike or avoidance of essential food groups.

Therefore, at worst vitamin and mineral supplementation acts as insurance against short and long-term dietary lapses, and guesswork in nutrient intake, including the ability to define the optimal diet. At best, using valid science to increase the nutrient content of available and typical food intakes may yield optimal functioning for an extended period, as compared to a non-supplemented state.

Introduction

The notion of vitamin and mineral supplementation, including the fortification of food, began with the intent to supply essential dietary nutrients significantly lacking in some geographical regions and to shore up inadequate nutrient content of the general population’s typical food intake to meet the Recommended Dietary Allowances (RDAs). Without supplementation, severe nutritional deficiencies would be widespread, as they once were.(1)

The RDAs are, by definition, “the levels of intake of essential nutrients that, on the basis of scientific knowledge, are judged by the Food and Nutrition Board to be adequate to meet the known (current) nutrient needs of practically all (97-98% of the population) healthy persons.”(2) They are not intended to be final, minimal or optimal. Rather, RDAs and the Dietary Guidelines are designed to prevent nutritional deficiencies by providing Americans with goals for adequate nutrient intake that most are not reaching.(3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11)

Dietary nutrient recommendations for achieving health are continuously being revised and generally trend upward as the scientific community gathers more data related to how different nutrient intake levels may affect overall health and longevity. Therefore, rather than simply updating the RDAs, which are set only for the average person to avoid deficiencies, the US Food and Nutrition Board, now an element of the Institute of Medicine, released the new Dietary Reference Intakes (DRIs) in 1994 and have updated them since. These evidence-based standards go beyond amending deficiencies; they also suggest the amount of nutrients needed for enhancing health. DRIs are as follows:

- Recommended Dietary Allowance (RDA) is the average daily dietary intake level that is sufficient to meet the nutrient requirements of nearly all (97 to 98 percent) healthy individuals in a specific life stage and gender group. The RDA is intended primarily for use as a goal for daily intake by individuals.(12)

- Estimated Average Requirement (EAR) is the daily intake value that is estimated to meet the requirement, as defined by the specified indicator of adequacy, in 50 percent of the individuals in a life stage or gender group. At this level of intake, the other 50 percent of individuals in a specified group would not have their nutritional needs met. The EAR is used in setting the RDA.(12)

- Adequate intake level (AI) is a value based on experimentally derived intake levels or approximations of observed mean nutrient intakes by a group (or groups) of healthy people.(12)

- Tolerable Upper Intake Level (UL) is the highest level of daily nutrient intake that is likely to pose no risks of adverse health effects in almost all individuals in the specified life stage group. As intake increases above the UL, the risk of adverse effects may increase. The intent is to set the UL so that it is below the threshold of even the most sensitive members of a group.(12)

However, despite the efforts of the scientific community, including the Food and Nutrition Board of the National Research Council and its DRIs, the general population is not meeting the majority of the requirements for vitamins and minerals. According to “What We Eat In America, NHANES,” Americans meet very few of the standards for dietary adequacy. (9) All recent nutrient intake survey have shown the same results: virtually no one gets the recommended amounts of all nutrients from food alone.(13)

Why the Inadequacies?

1. The majority of the general population does not have the ability to properly analyze foods, much less buy, prepare and consume each in the proper array to meet daily requirements.(14,15).

2. Today’s sedentary environment, which is promoted by increasingly inactive jobs, convenient forms of communication, easy access to food, comfort and entertainment, prohibits most of the general population from consuming the calories necessary to reach these recommended nutrient levels without gaining weight.(16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29) In addition, because of the lack of movement in today’s society, the large portion of the American adult population participating in weight reducing diets are forced to severely restrict food intake in order to sustain weight loss, a condition that all but assures nutrient inadequacies without supplementation.(30,31,32)

3. In general, food preferences established early in life keep people from more diverse nutritional choices. For most, the early introduction of sugar and fatty convenient foods (e.g. fast food outlets) creates addictions to these types of food, leaving many undernourished in terms of the RDAs for the long term. In other words, the foods most people normally choose are high in energy but low in nutrients.(33,34,35)

4. Available nutritional information regarding particular foods is not necessarily accurate. The true nutritional content of a given food is dependent upon such factors as its origin, time and maturity of its harvest, slaughter, cooking method, processing, and shelf life.(13,36,37)13 In addition, any calculations are vulnerable to analytical error.(38,39) These factors illustrate that just because a list of nutrients associated with a food is published, those nutrients are not guaranteed to actually enter the body. Performing an ingredient test on each food before it enters the body is not a practical solution.

Vitamin and mineral losses become cumulative. While an argument can be made that the RDAs include a margin of safety to address some of these problems, many of the RDAs are established as “sub-optimal,” as demonstrated by the continual upward trend.(40,41) No margin of safety can compensate for a nearly complete lack of an essential nutrient due to any of the above factors, especially soil content. This was illustrated, though inadvertently, in a study conducted by Clark, Combs and Turnbull.(42) The study’s subjects were selected from a region in the United States where there is little to no selenium in the soil. The dramatic cancer preventative benefits witnessed in the selenium-supplemented group compared to the placebo users are most likely attributed to the lack of selenium in the food supply from this area. All these uncontrollable issues become the strongest argument in support of the current scientific approach that no matter how well you plan your diet, you need “insurance.”(43,44,45)

Even trained professionals struggle with guidelines. In a 1995 study published in the Journal of the American Dietetic Association,(46) dietitians were asked to design diets that met the 1989 RDAs and 1990 Dietary Guidelines while providing 2200-2400 calories (the average non-athletic female gains weight at 1800 calories)(47) and remaining palatable to the individuals in the study. Using software designed specifically for creating a healthy diet, these trained dietitians were unable to accomplish the objective.(46) If health professionals cannot consistently reach the RDAs and dietary guidelines within an average amount of calories that promotes leanness while being universally palatable, how is the general public expected to do so?

Poor nutrition has been linked to an increased risk of many diseases including cancer, heart disease, and diabetes. One highly regarded researcher proposes that nutrient inadequacies may actually illicit a triage response where the body would prioritize the use of lacking nutrients by urgency which, if true, would accelerate cancer, aging, and neural decay but would leave critical metabolic functions intact; basically favoring short-term survival at the expense of long-term health.(48)

Collectively, the aforementioned circumstances strongly suggest nutrient augmentation to food intake in order to meet the existing DRIs, which still may not be optimal (40,41,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,6566,67,68) but are adequate for avoiding deficiency diseases.

Discussion

The original paradigm based on nutritional essentiality is undergoing a shift. Many well-informed health professionals and well-respected institutions are breaking precedent by recommending the use of a multiple vitamin and mineral supplement (VMS) in conjunction with a well-balanced diet.(43,44,48,69,70,71) Aside from the “insurance” value, the changing views on VMS recommendations are also a result of ongoing research into the amount of a nutrient required to prevent a chronic disease from occurring, rather than simply preventing a deficiency state.(2,63,72,73,74,75,76,77) These revised recommendations led to the reconstruction of the RDAs into the Dietary Reference Intakes (DRI).(2,12,78,79,80)

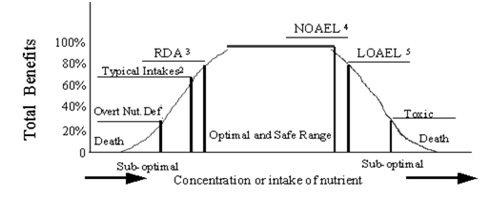

RDA levels of specific nutrients will continue to be revised, and wide ranges of safe and potentially effective intakes established (see Figure 1). This makes it nearly impossible for the general population to reach potentially beneficial amounts while remaining within a calorie level that would promote healthy body fat levels without supplementation.(47,49,74,81,82,83) The DRIs provide a new framework within which recommendations of nutrient intake and clear health benefits can be established.

Establishing beneficial nutrient levels with little to no risk

The issue still pending is just how much of each nutrient is needed, in general, to receive an optimal physiological response that fulfills the potential for health and performance. Though these exact amounts are currently unknown and will always vary by individual, volumes of information exist on approximate values within a wide range of safety that suggest efficacy for the general population.40,41 In other words, the benefits of doses properly extrapolated from current research would greatly outweigh any unlikely risks from these doses, especially when compared to the risks resulting from no supplementation at all.

Using information available today, we must consider three levels of nutrient activity:

1. The amount of the nutrient to prevent overt deficiency disease.(14)

- Approximately between two-thirds of the current RDAs and the actual RDAs.

2. When applicable, the amount of a nutrient that may support optimal benefits.

(42,53,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,84,85)

- Approximately between the current RDAs and the No Observed Adverse Effect Level (NOAEL).

3. The amount of a nutrient that may cause adverse reactions.(40,41,86)

- Lowest Observed Adverse Effect Level (LOAEL) and higher.

Figure 1 illustrates how, within a wide range of safety, the amount of a nutrient required to achieve optimal benefits in performance and health can be approximated. As the concentrations of nutrient intake increases, different levels of biological function (total benefits) are approached.

Figure 1: Ultimate Goal of Nutrient Augmentation

1. Overt nutritional deficiency.

2. Typical intakes (2/3 of RDA, thus sub-optimal).

3. The RDAs, which we have established as sub-optimal for many nutrients.

4. NOAEL -- A safe intake greater than the RDAs, and it is likely between this nutrient amount and its RDA where the optimal level of intake exists.

5. LOAEL – An intake that is not safe for all consumers therefore should generally be considered sub-optimal.

Safe and beneficial dosages

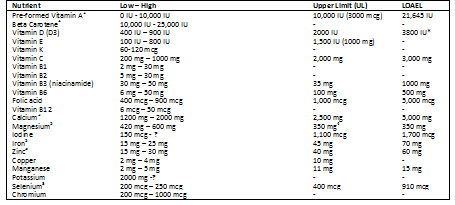

Cautious review of existing information following the criteria in Figure 1 suggests total nutrient intake to fall somewhere within the ranges shown in Table 1. Any nutrient not appearing in the table indicates that too little information exists to establish a range. Therefore, consuming a balanced diet will presumably meet the currently known need. These totals include the nutrient content of food intake and supplementation. Considering most nutrient ranges shown in Table 1 fall well within known safety margins and the often small contribution food makes to most of these desired levels, it would generally not be necessary for individuals to compile the nutrient content of daily food intake. Respecting this, daily supplementation should be no higher (maybe lower when marked) than the upper amount listed, which is commonly well below the tolerable upper limit. More active individuals may maintain intakes closer to the higher side of the range. Recently, it has been proposed that the age and gender of an adult determines the appropriate levels of certain nutrients.

These doses, even at the high end, are meant to enhance natural physiology (fulfilling potential related to health). They are not in pharmacological amounts that would be used to treat symptoms of disease. The use of vitamins and minerals for therapy should be conducted by a qualified physician.

Table 1:

Table 1: Safe and Probable Optimal Range Including Food Sources

1. Supplemental amount can be zero if daily intake of beta carotene is within the safe and optimal range.

2. Smokers, those likely to develop, or those that already have lung cancer, should avoid beta carotene supplementation.

3. Upper range amount is from supplements only.

4. From supplements only.

5. Supplemental amounts should be close to the low numbers shown

* Currently being revisited.

Chronic ingestion of nutrients anywhere in the range illustrated in Table 1 has been established as safe for the general population and may prove to be highly beneficial.

Proper intake

The synergy of these nutrients, including their daily levels, require they be consumed together but distributed as equally throughout a 24-hour period as possible to avoid over-saturation and losses. Individuals should start by following a healthy food plan as closely as possible, including a calorie intake that promotes healthy body fat levels, and adding a controlled-release multiple vitamin and mineral preparation to meet the appropriate nutrient levels.

Using an acceptable pill size, these amounts could be reached through ingestion of a multiple vitamin and mineral formula one to two times daily with meals. Generally, a separate calcium and Vitamin D supplement may need to be included in order to reach desired levels, which would also be consumed in split doses. This method helps maintain tissue target levels throughout the day, as opposed to consuming the total amount at one time which would diminish the desired result.

Conclusion

Vitamins and minerals ingested as described may allow the body to operate at full capacity without disturbing its natural physiology. The belief that individuals consume each health and performance-related compound in optimal doses, ratios and at proper times from food every day is unfounded, especially when all obstacles are taken into account, including the inability to define these levels. In addition, it is common knowledge that the general population does not consume more than what is needed of all necessary substances in their diets. These issues collectively indicate that any nutrient contributing to cellular health and perform¬ance has the potential to be lacking when food is the only delivery system.

Because of the safety margins of most nutrients, and paying strict attention to tolerable upper limits, distinctions can be made between the strongest possible evidence and instances where the evidence becomes strong enough regarding ingesting levels of nutrients that show potential in staving off chronic disease. In other words, when supplementing properly, potential benefits would greatly outweigh any unlikely risks. Therefore, at worst vitamin and mineral supplementation acts as insurance against short and long term dietary lapses, and guesswork in nutrient intake, including the ability to define the optimal diet. At best, using valid science to increase the nutrient content of available and typical food intakes may yield optimal functioning for an extended period, as compared to a non-supplemented state.

Content utilized by permission from The National Academy of Sports Medicine.

References

1. McCollum EV. A History of Nutrition. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co.;1957 (Chapters 14-20, 27).

2. Institute of Medicine, Food and Nutrition Board. How should the recommended dietary allowances be revised? Washington, DC: National Academy Press, 1994.

3. Frary CD, Johnson RK, Wang MQ. Children and adolescents' choices of foods and beverages high in added sugars are associated with intakes of key nutrients and food groups. J Adolesc Health. 2004 Jan;34(1):56-63.

4. Guenther PM, Dodd KW, Reedy J, Krebs-Smith SM. Most Americans eat much less than recommended amounts of fruits and vegetables. J Am Diet Assoc. 2006 Sep;106(9):1371-9.

5. Hanson NI, Neumark-Sztainer D, Eisenberg ME, Story M, Wall M. Associations between parental report of the home food environment and adolescent intakes of fruits, vegetables and dairy foods. Public Health Nutr. 2005 Feb;8(1):77-85.

6. Kranz S, Siega-Riz AM, Herring AH. Changes in diet quality of American preschoolers between 1977 and 1998. Am J Public Health. 2004 Sep;94(9):1525-30.

7. Mannino ML, Lee Y, Mitchell DC, Smiciklas-Wright H, Birch LL. The quality of girls' diets declines and tracks across middle childhood. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2004 Feb 27;1(1):5.

8. Suitor CW, Gleason PM. Using Dietary Reference Intake-based methods to estimate the prevalence of inadequate nutrient intake among school-aged children. J Am Diet Assoc. 2002 Apr;102(4):530-6.

9. Department of Agriculture (US). Factsheet on What We Eat in America NHANES 2005-2006. http://www.ars.usda.gov/Services/docs.htm?docid=17041

10. Serdula MK, Gillespie C, Kettel-Khan L, Farris R, Seymour J, Denny C. Trends in fruit and vegetable consumption among adults in the United States: behavioral risk factor surveillance system, 1994-2000. Am J Public Health. 2004 Jun;94(6):1014-8.

11. Beals KA. Eating behaviors, nutritional status, and menstrual function in elite female adolescent volleyball players. J Am Diet Assoc. 2002 Sep;102(9):1293-6.

12. Murphy SP, Barr SI. "Dietary Reference Intakes for Vitamins." Handbook of Vitamins. Ed. Zempleni J et al. CRC Press: Boca Raton, 2007. 560-561.

13. Briefel RR, Johnson CL. Secular trends in dietary intake in the United States. Annu Rev Nutr. 2004;24:401-31. Review.

14. Murphy SP, Barr SI. Challenges in using the dietary reference intakes to plan diets for groups. Nutr Rev. 2005 Aug;63(8):267-71. Review.

15. Kuehn BM. Experts charge new US dietary guidelines pose daunting challenge for the public. JAMA. 2005 Feb 23;293(8):918-20.

16. Kim SH, Kim HY, Kim WK, Park OJ. Nutritional status, iron-deficiency-related indices, and immunity of female athletes. Nutrition. 2002 Jan;18(1):86-90.

17. Wang MC, Cubbin C, Ahn D, Winkleby MA. Changes in neighbourhood food store environment, food behaviour and body mass index, 1981--1990. Public Health Nutr. 2008 Sep;11(9):963-70. Epub 2007 Sep 26.

18. Nead KG, Halterman JS, Kaczorowski JM, Auinger P, Weitzman M. Overweight children and adolescents: a risk group for iron deficiency. Pediatrics. 2004 Jul;114(1):104-8.

19. Lowry R, Lee SM, McKenna ML, Galuska DA, Kann LK. Weight management and fruit and vegetable intake among US high school students. J Sch Health. 2008 Aug;78(8):417-24; quiz 455-7.

20. Bachman JL, Reedy J, Subar AF, Krebs-Smith SM. Sources of food group intakes among the US population, 2001-2002. J Am Diet Assoc. 2008 May;108(5):804-14.

21. Park J, Beaudet MP. Eating attitudes and their correlates among Canadian women concerned about their weight. Eur Eat Disord Rev. 2007 Jul;15(4):311-20.

22. Hill AJ. Motivation for eating behaviour in adolescent girls: the body beautiful. Proc Nutr Soc. 2006 Nov;65(4):376-84. Review.

23. Malinauskas BM, Raedeke TD, Aeby VG, Smith JL, Dallas MB. Dieting practices, weight perceptions, and body composition: a comparison of normal weight, overweight, and obese college females. Nutr J. 2006 Mar 31;5:11.

24. Jankauskiene R, Kardelis K, Pajaujiene S. Body weight satisfaction and weight loss attempts in fitness activity involved women. J Sports Med Phys Fitness. 2005 Dec;45(4):537-45.

25. Harris MB. Weight concern, body image, and abnormal eating in college women tennis players and their coaches. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab. 2000 Mar;10(1):1-15.

26. Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Curtin LR, McDowell MA, Tabak CJ, Flegal KM. Prevalence of overweight and obesity in the United States, 1999-2004. JAMA. 2006 Apr 5;295(13):1549-55.

27. JD Wright, MPH, J Kennedy-Stephenson, MS, CY Wang, PhD, MA McDowell, MPH, CL Johnson, MSPH. Trends in Intake of Energy and Macronutrients --- United States, 1971—2000. National Center for Health Statistics, CDC. February 6, 2004 / 53(04);80-82

28. Gabel KA. Special nutritional concerns for the female athlete. Curr Sports Med Rep. 2006 Jun;5(4):187-91. Review.

29. Ziegler P, Sharp R, Hughes V, Evans W, Khoo CS. Nutritional status of teenage female competitive figure skaters. J Am Diet Assoc. 2002 Mar;102(3):374-9.

30. Dwyer JT, Allison DB, Coates PM. Dietary supplements in weight reduction. J Am Diet Assoc. 2005 May;105(5 Suppl 1):S80-6. Review.

31. National Institutes of Health. Clinical Guidelines on the Identification, Evaluation, and Treatment of Overweight and Obesity in Adults—The Evidence Report. National Institutes of Health. Obes Res. 1998; 6(suppl 2):S51-S209.

32. Cifuentes M, Riedt CS, Brolin RE, Field MP, Sherrell RM, Shapses SA. Weight loss and calcium intake influence calcium absorption in overweight postmenopausal women. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;80:123-130.

33. Harnack L, Walters SA, Jacobs DR Jr. Dietary intake and food sources of whole grains among US children and adolescents: data from the 1994-1996 Continuing Survey of Food Intakes by Individuals. J Am Diet Assoc. 2003 Aug;103(8):1015-9.

34. Frary CD, Johnson RK, Wang MQ. Children and adolescents' choices of foods and beverages high in added sugars are associated with intakes of key nutrients and food groups. J Adolesc Health. 2004 Jan;34(1):56-63.

35. Guthrie JF, Morton JF. Food sources of added sweeteners in the diets of Americans. J Am Diet Assoc. 2000 Jan;100(1):43-51.

36. Stampher MJ. Vitamin and Minerals, What you need to know. Harvard Medical School. 2006.

37. Bouis HE. Enrichment of food staples through plant breeding: a new strategy for fighting micronutrient malnutrition. Nutrition. 2000 Jul-Aug;16(7-8):701-4. Review.

38. Combs GF. The vitamins, fundamental aspects in nutrition and health. Second Edition. San Diego: Academic Press; 1998. Pp. 469-79.

39. Conway JM, Rhodes DG, Rumpler WV. Commercial portion-controlled foods in research studies: how accurate are label weights? J Am Diet Assoc. 2004 Sep;104(9):1420-4.

40. Hathock JN. Vitamins and minerals: efficacy and safety. Am J Clin Nutr 1997 Aug; 66(2):427-37.

41. Hathock JN. Vitamins and mineral Safety. 2nd Edition. Council for Responsible Nutrition. 2004.

42. Clark LC, Combs GF Jr., Turnbull BW. The nutritional prevention of cancer with selenium 1983-1993; a randomized clinical trial. FASEB J 1996;10:A550 (abstr).

43. Liebman B, Schardt D. The multivitamin maze. Nutrition Action Newsletter: Center for Science in Public Interest (CSPI) 2006 March 33(2):6-10.

44. Fairfield KM, Fletcher RH. Vitamins for chronic disease prevention in adults: scientific review. JAMA. 2002 Jun 19;287(23):3116-26. Review. Erratum in: JAMA 2002 Oct 9;288(14):1720.

45. Barrett J. What the Nutrition Experts Take Every Day. Five experts talk about what they take and offer tips for getting the vitamins and nutrients you need. Newsweek. January 16, 2006.

46. Dollahite J, Franklin D, McNew R. Problems encountered in meeting the Recommended Dietary Allowances for menus designed according to the Dietary

Guidelines for Americans. J Am Diet Assoc 1995 Mar;95(3):341-4, 347.

47. JD Wright, MPH, J Kennedy-Stephenson, MS, CY Wang, PhD, MA McDowell, MPH, CL Johnson, MSPH. Trends in Intake of Energy and Macronutrients --- United States, 1971—2000. National Center for Health Statistics, CDC. February 6, 2004 / 53(04);80-82

48. Ames BN. Low micronutrient intake may accelerate the degenerative diseases of aging through allocation of scarce micronutrients by triage. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006 Nov 21;103(47):17589-94. Epub 2006 Nov 13. Review.

49. Chandra RK. Effect of vitamin and trace-element supplementation on immune responses and infection in elderly subjects. Lancet 1992 Nov 7;340(8828):1124-

7.

50. Russell RM. New views on the RDAs for older adults. J Am Diet Assoc 1997 May;97(5):515-8.

51. Linus Pauling Institute. Micronutrient Research for Optimum Health. Oregon State University. http://lpi.oregonstate.edu/infocenter/vitamins/VitaminC/index.html. Accessed 09/08/2006.

52. Atalay M, Lappalainen J, Sen CK. Dietary antioxidants for the athlete. Curr Sports Med Rep. 2006 Jun;5(4):182-6. Review.

53. Rimm EB, Willett WC, Hu FB, Sampson L, Colditz GA, Manson JE, Hennekens C, Stampfer MJ. Folate and vitamin B6 from diet and supplements in relation to risk of coronary heart disease among women. JAMA 1998 February 4;279(5):359-364.

54. Woodside JV, Yarnell JWG, McMaster D, Young IS, Harmon DL, McCrum EE, Patterson CC, Gey KF, Whitehead AS, Evans A. Effect of B-group vitamins and antioxidant vitamins on hyperhomocysteinemia: a double-blind, randomized, factorial-design, controlled trial 1-3. Am J Clin Nutr 1998;67:858-66.

55. Moore CE, Murphy MM, Holick MF. Vitamin D intakes by children and adults in the United States differ among ethnic groups. J Nutr. 2005 Oct;135(10):2478-85.

56. Chernoff R. Micronutrient requirements in older women. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005 May;81(5):1240S-1245S. Review.

57. Gennari C. Calcium and vitamin D nutrition and bone disease of the elderly. Public Health Nutr. 2001 Apr;4(2B):547-59. Review.

58. Sherwood KL, Houghton LA, Tarasuk V, O'connor DL. One-third of pregnant and lactating women may not be meeting their folate requirements from diet alone based on mandated levels of folic Acid fortification. J Nutr. 2006 Nov;136(11):2820-6.

59. Bischoff-Ferrari HA, Willett WC, Wong JB, Giovannucci E, Dietrich T, Dawson-Hughes B. Fracture prevention with vitamin D supplementation: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. JAMA. 2005 May 11;293(18):2257-64. Review.

60. Holick MF. The vitamin D epidemic and its health consequences. J Nutr. 2005 Nov;135(11):2739S-48S.

61. Grant WB, Holick MF. Benefits and requirements of vitamin D for optimal health: a review. Altern Med Rev. 2005 Jun;10(2):94-111. Review.

62. Frank B, Gupta S. A review of antioxidants and Alzheimer's disease. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2005 Oct-Dec;17(4):269-86. Review.

63. Hollis BW. Circulating 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels indicative of vitamin D sufficiency: implications for establishing a new effective dietary intake recommendation for vitamin D. J Nutr. 2005 Feb;135(2):317-22. Review.

64. Palacios C. The role of nutrients in bone health, from a to z. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2006;46(8):621-8.

65. Morton DJ, Barrett-Connor EL, Schneider DL. Vitamin C supplement use and bone mineral density in postmenopausal women. J Bone Miner Res. 2001 Jan;16(1):135-40.

66. Kantoff P. Prevention, complementary therapies, and new scientific developments in the field of prostate cancer. Rev Urol. 2006;8 Suppl 2:S9-S14.

67. Dunn-Emke SR, Weidner G, Pettengill EB, Marlin RO, Chi C, Ornish DM. Nutrient adequacy of a very low-fat vegan diet. J Am Diet Assoc. 2005 Sep;105(9):1442-6.

68. Volpe SL. Micronutrient requirements for athletes. Clin Sports Med. 2007 Jan;26(1):119-30. Review.

Group breaks precedent [National Academy of Sciences], recommends vitamins. The Washington Post 1998 April 8; Sect A:14.

69. Schoenthaler SJ, Bier ID, Young K, Nichols D, Jansenns S. The effect of vitamin-mineral supplementation on the intelligence of American schoolchildren: a

randomized, double-blind placebo-controlled trial. J Altern Complement Med. 2000 Feb;6(1):19-29.

70. Liebman B, Schardt D. Vitamin smarts. Nutrition Action Newsletter: Center for Science in Public Interest (CSPI) 1995 November 22(9):1,6-10.

71. Holick MF. The vitamin D epidemic and its health consequences. J Nutr. 2005 Nov;135(11):2739S-48S.

72. Grant WB, Holick MF. Benefits and requirements of vitamin D for optimal health: a review. Altern Med Rev. 2005 Jun;10(2):94-111. Review.

73. Frank B, Gupta S. A review of antioxidants and Alzheimer's disease. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2005 Oct-Dec;17(4):269-86. Review.

74. Hollis BW. Circulating 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels indicative of vitamin D sufficiency: implications for establishing a new effective dietary intake

recommendation for vitamin D. J Nutr. 2005 Feb;135(2):317-22. Review.

75. Morton DJ, Barrett-Connor EL, Schneider DL. Vitamin C supplement use and bone mineral density in postmenopausal women. J Bone Miner Res. 2001

Jan;16(1):135-40.

76. Kantoff P. Prevention, complementary therapies, and new scientific developments in the field of prostate cancer. Rev Urol. 2006;8 Suppl 2:S9-S14.

77. Kennedy ET. Evidence for nutritional benefits in prolonging wellness. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006 Feb;83(2):410S-414S. Review.

78. Yates AA. National nutrition and public health policies: issues related to bioavailability of nutrients when developing dietary reference intakes. J Nutr. 2001 Apr;131(4 Suppl):1331S-4S.

79. Yates AA. Dietary reference intakes: concepts and approaches underlying protein and energy requirements. Nestle Nutr Workshop Ser Pediatr Program. 2006;(58):79-90; discussion 90-4. Review.

80. Blackburn GL, Jensen GL. Improvement of coronary artery disease in a patient with hyperhomocysteinemia: report of a case. Nutrition 1998;14.

81. Cheng CH, Lin PT, Liaw YP, Ho CC, Tsai TP, Chou MC, Huang YC. Plasma pyridoxal 5'-phosphate and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein are independently associated with an increased risk of coronary artery disease. Nutrition. 2008 Mar;24(3):239-44.

82. Akabas SR, Deckelbaum RJ. N-3 Fatty acids: Recommendations for Theraeutics and Prevention. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006 Jun;83(6 Suppl):1451S-1538S.

83. Schauss AG. Minerals, trace elements and human health. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data.

84. Combs GF. The vitamins, fundamental aspects in nutrition and health. Second Edition. San Diego: Academic Press; 1998. Pp. 522-529.

85. Combs GF. The vitamins, fundamental aspects in nutrition and health. Second Edition. San Diego: Academic Press; 1998. Pp. 537-548.